Peeking / Endogenous Stopping¶

There is often a temptation when running experiments to watch the data roll in as the experiment runs so you can stop the experiment early if the results look good, a practice known as “peeking.” In AB testing, you may watch because it’s easy or because your boss wants answers yesterday; in medical studies, you may watch because the trial is expensive, and you’d like to stop as soon as you can, or because you want to know if lots of patients start experiencing negative side effects. Checking the results of your experiment as the data rolls in and stopping the experiment early if your experiment shows a statistically significant effect is called and it is VERY bad.

Ending an experiment because of the intermediate results look good is what’s called “stopping endogenously,” and it will render your experiment statistically invalid. Why? The math on this gets very complicated, but the basic idea is that the apparent results of your experiment will fluctuate over time (your p-value is a random variable). As a result, if you let your experiment run long enough, at some point one of those fluctuations will make the experiment look statistically significant. Normally that’s fine—it’s part of why we talk about p-values in probabilistic terms. But that’s because we aren’t choosing to stop because of the p-value. If, however, we choose to stop our experiment when we see one of those fluctuations, we’re deliberately selecting an outlier moment, and… well, it will be an outlier!

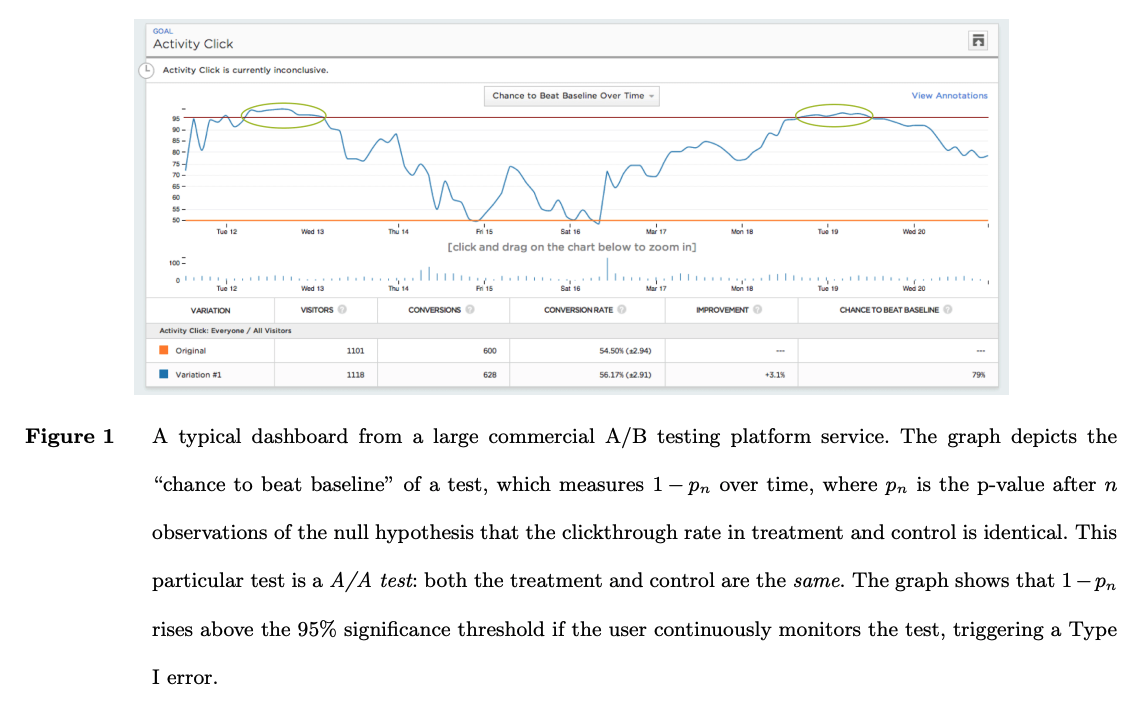

To illustrate this point, Ramesh Johari, Leo Pekelis, and David Walsh created a great illustration where they ran a fake A/B test on a large website in which the two treatment conditions (A and B) were exactly the same (so really it was an A/A test). They ran this over several days, then plotted – for each moment in time – whether the data would say A is better than B if the experiment were stopped and analyzed at that time. As the figure shows, over the long run the data shows there’s no significant difference between A and B; but there are moments where random fluctuations make the difference look significant. So if you had chosen to stop the experiment as soon as you hit one of those moments, you’d be in deep trouble!

To be clear, that doesn’t mean there aren’t ways you can stop experiments early based on results—in fact your next reading is about how they do that at Netflix!––but don’t do it unless you really understand the statistics (even if your boss really wants to!).